Several times a year, before Covid-19 arrived, I visited the preschool where I used to teach to take dictation of a poem from each child, to recite and read poems, and to talk about poetry. Instead, in the thick of the pandemic, I put together the first of these at-home poetry activities. Then kept adding … Now I use them in the classroom again.

Starting by reading and reciting a model poem (or two) several times and asking the children to join in reciting as soon as they think they have any of the words gets us into the music, and everyone feeling a rhythm inside their bodies. Add to and subtract from my methods as suits your purpose.

13 POETRY ACTIVITES (Scroll down for the latest)

- A RECIPE/DEFINITION POEM and WONDERFUL POETRY BOOKS FOR CHILDREN

- AN OUTSIDE-THE-WINDOW POEM

- A WISH-I-WERE-THERE PARTIAL CENTO

- A BLOTTO or GOBOLINK POEM

- A DREAM POEM

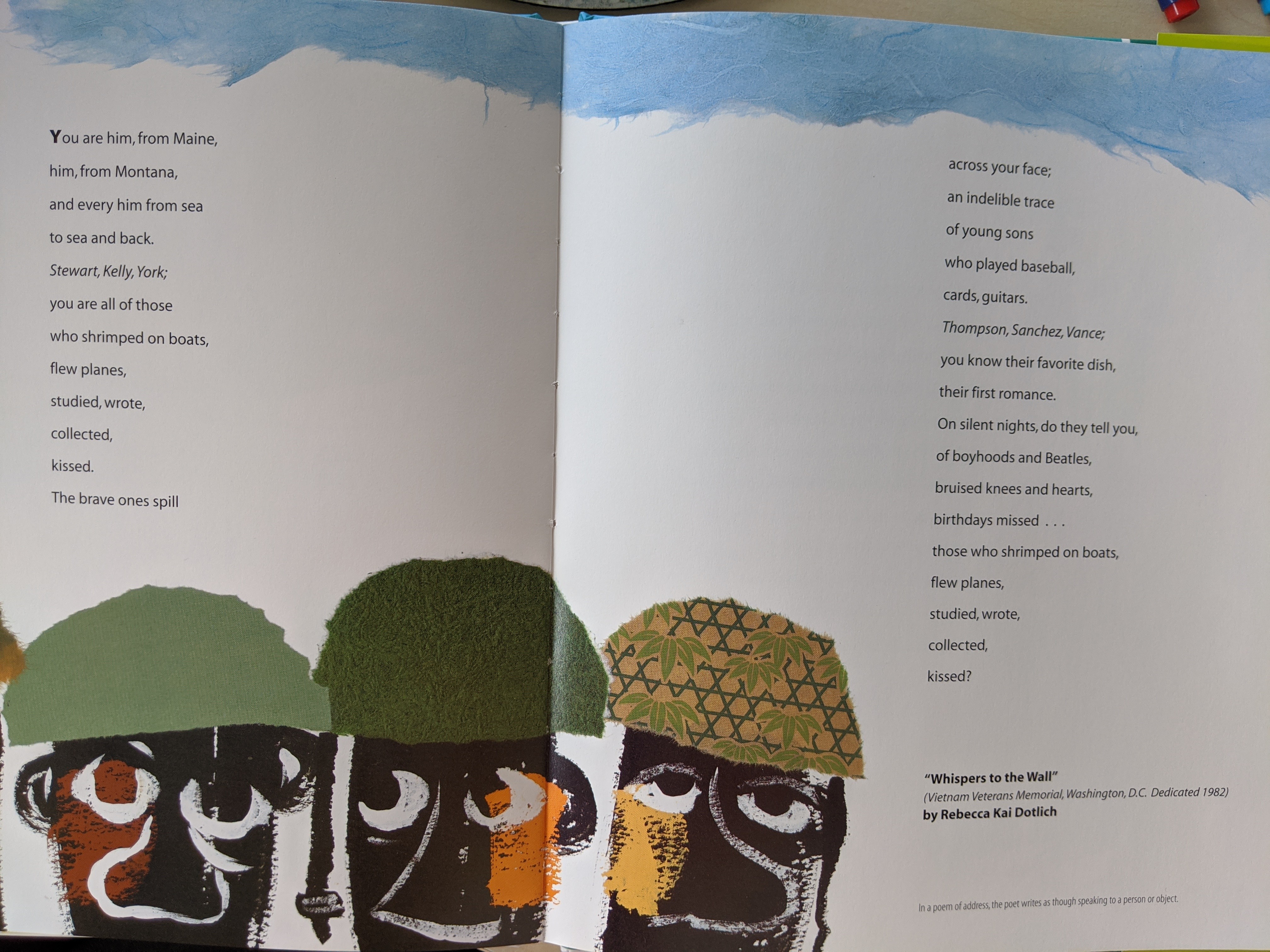

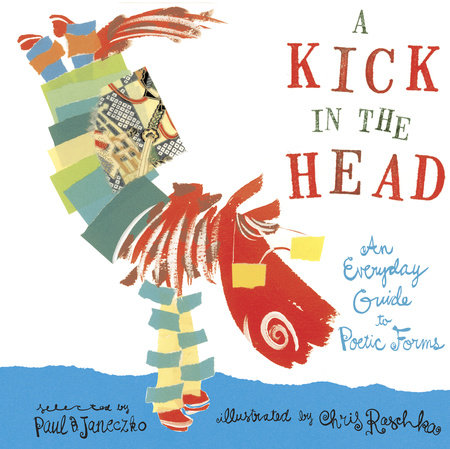

- A POEM OF DIRECT ADDRESS

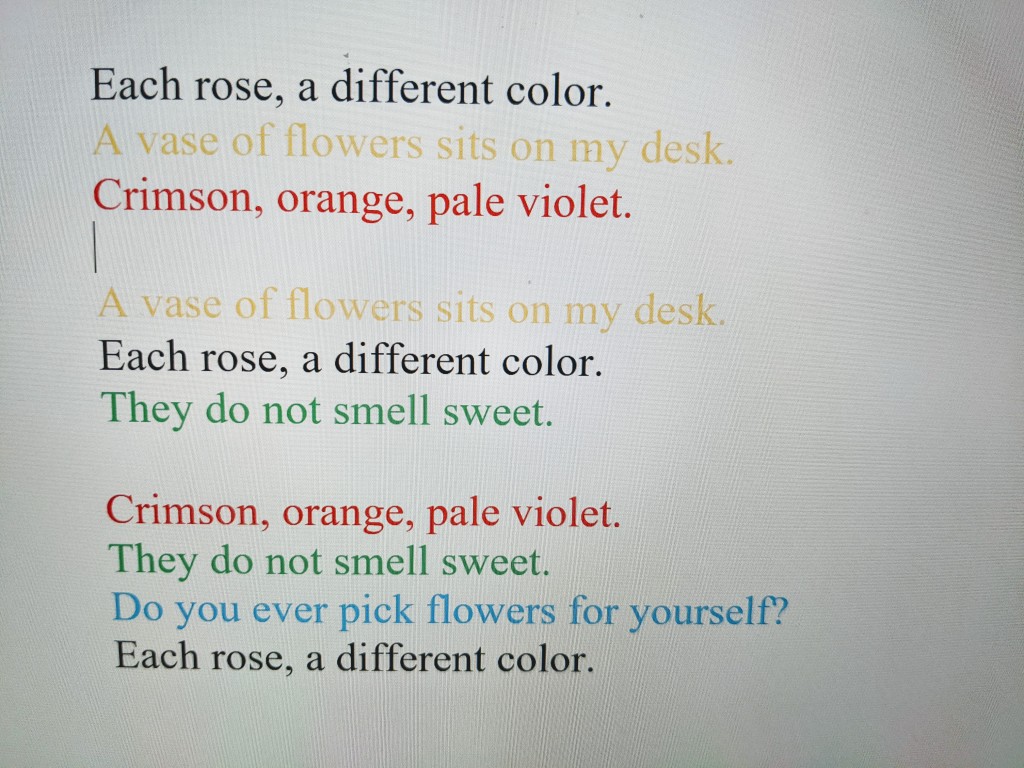

- A LEXICON POEM

- A TWO-MINUTE POEM

- A PATTERN POEM

- A LOVE POEM and VIDEO: ME AND BRET ELLERTON TALKING POETRY

- A SOUND POEM

- AN ABECEDARIAN POEM

- A PLAY POEM

- A RECIPE/DEFINITION POEM

To start: I read and recite the model poem (or two, in this case) several times, asking the children to join me as soon as they think they have any of the words. Besides getting us into the musical and rhythmic aspects of poems, here it is also to show how a recipe/definition poem can be constructed, that they don’t have to be about food. The Rossetti is fun to act out.

Mix a Pancake by Christina Rossetti

Mix a pancake,

Stir a pancake,

Pop it in the pan;

Fry the pancake,

Toss the pancake–

Catch it if you can.

How to Make a Morning by Elaine Magliaro

Melt a galaxy of stars

in a large blue bowl.

Knead the golden sun

and let it rise in the East.

Spread the sky

with a layer of lemony light.

Blend together

until brimming with brightness.

Fold in dewdrops.

Sprinkle with songbirds.

Garnish with a chorus

of cock-a-doodle-doos.

Set out on a platter at dawn

and enjoy.

I like to point out that the verbs are telling the reader what to do. Your child’s poem is to tell readers how to do something, to make a kind of food or something abstract, like the morning.

When I meet with each child, I ask, Do you know what you want your poem to be about? If not, I suggest things with questions. Is there some kind of food you really like that you’d like it to be about? What about a thing? Do you want to tell how to be: strong, brave, patient, loving, kind, silly, friendly, happy, etc…? Or how to be a friend, how to build a tower, how to comfort Baby Sister, etc…?

Once they’ve chosen the thing, I write down their words, verbatim, as they tell me their answers to, What ingredients do you need to make ____? How much of each do you need? (I return to each ingredient to insert this.) What do you have to do to the ingredients–this is where I might say, Remember in making the morning, the poet blended, and folded, and sprinkled? How long do you have to do that? (As in “until brimming with brightness.”) How do you tell when you’re finished making it?

Stick to imperatives! (Mix, stir, fry, toss, catch, and so forth.) When that’s not how it comes out of the child’s mouth, I ask, How would you tell someone how to do it?

For a final line, I often like to ask the poet for a turn, maybe something funny or unexpected. The final line could be to tell the reader what to do once the recipe is finished–as in, “Eat it!”

I read back the dictated material and ask if the poet wants to add anything, repeat anything, move anything around, take anything away. Then read it back again. I usually pick the line breaks and format.

Capable writers may wish to scribe for themselves. They may wish to crib the shape of these example poems as templates. If they choose this approach, please, encourage them to add, “After How to Make a Morning …”

I’d be thrilled if you wished to share any products in the comments section, below.

WONDERFUL POETRY BOOKS FOR CHILDREN

Poetry collections I often read from when teaching poetry:

The Bill Martin Jr Big Book of Poetry with a forward by Eric Carle.

Fiction about Poetry: Both of these are beautiful books.

The Bat-Poet by Randall Jarell, pictures by Maurice Sendak. It is longer than a picture book, shorter than a chapter book.

This Is a Poem that Heals Fish by Jean-Pierre Simeon (a picture book). It is a child’s journey to understanding what a poem might be so he can give one to his fish who is dying of boredom.

2. AN OUTSIDE-THE-WINDOW POEM

Look outside or think about what is outside your home. Choose something not made by people as the subject of your poem. A dog? The sky? Humidity? A tree? Ask yourself why you picked this thing. What do you know about it? How do you feel about it? What do you wonder about it? Why is it important to you? Why might it matter to someone else? You could make each answer a line of your poem, follow this template, or go your own directions!

1st line: Name a true thing about it. (For example: color, shape, location)

2nd line: Name another true thing about it.

3rd line: Say how you feel about it. (A strong emotion or wish.)

4th line: Ask a question about it.

5th line: Say why it might matter to someone else.

An Outside-the-Window Poem by Emily Dickinson

XCVII

To make a prairie

It takes a clover and a bee,–

One clover and a bee,

And revery.

Revery alone will do

If bees are few.

A nifty website about writing poetry with a lesson on writing outside: https://powerpoetry.org/resources/poem-about-surroundings

3. A WISH-I-WERE-THERE PARTIAL CENTO

If a cento is a patchwork made of lines from other people’s poems, then a partial cento is a poem that sews in one line from someone else’s poem or story.

Choose a place where you wish you were. It might be where you are. It might be a place in your imagination. It might be a place you are unable to get to right now. Maybe you’d like to draw the place to think about it more and to prompt your poem.

To build this poem you can follow the same steps as with “AN OUTSIDE-THE-WINDOW POEM,” above, by making your answers to these questions into the lines of your poem, using the template, or going your own directions. Each step of the template might involve more than one line of your poem.

What is the place? Why did you pick this place? What is it like? Hot? Sunny? Wild? Near? Made up? How do you feel about it? Have you been there? When do you go there or when do you think about going there? What do you wonder about it? Why is it important to you? How is it different to be there instead of where you are?

- Name the spot, as if you are in it.

- Describe the place with colors or smells or three things you find there.

- Say how you feel about this place.

- Say when you will next go there.

- Say what might be the same or might be different the next time you are there (in reality or your imagination).

When you have your lines, at random open the book you are reading. Put your finger on the page. Do you like this line? If so, use the words from this spot as a line in you poem. If not, repeat the process until you find a line you like. (I just did this and my finger landed on “I had trouble with this place.” !!!!)

Now read over/listen to your lines. Are they in the right order for you? Arrange them. Rearrange them. Try various orders until you like the sound and look of your poem. Some poets cut their lines into strips for this part.

A Wish-I-Were-There Partial Cento

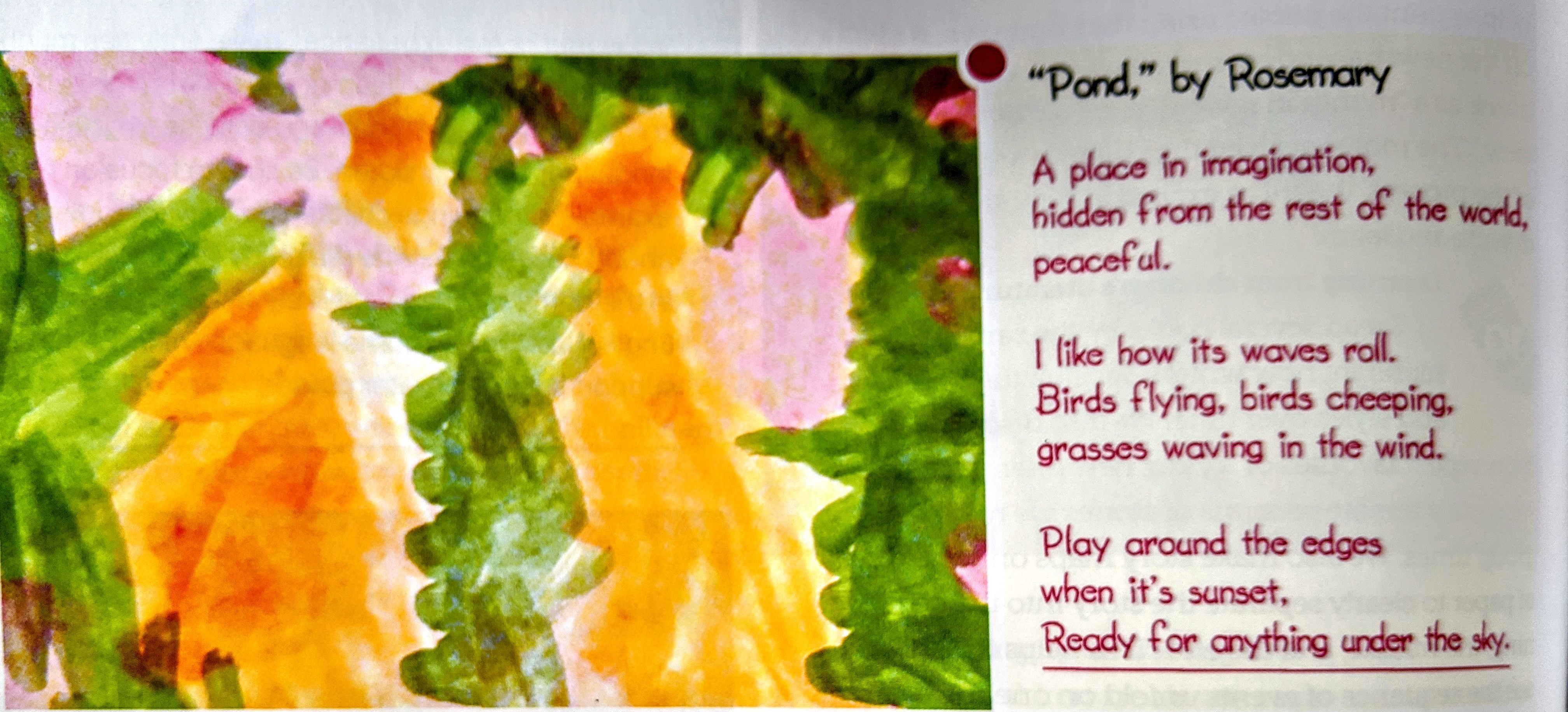

Pond by Rosemary

The final line of Rosemary’s poem comes from Dr. Seuss’s Oh, The Places You’ll Go! The illustration is hers too. Rosemary began by painting a place where she wanted to go. She was a student of mine many years ago. This image and her poem appeared in “Writing Poetry with Preschoolers” in Teaching Young Children.

Billy Collins describes how to write a conventional cento: https://www.masterclass.com/articles/how-to-write-patchwork-poems#what-is-a-cento-poem

4. A BLOTTO or GOBOLINK POEM

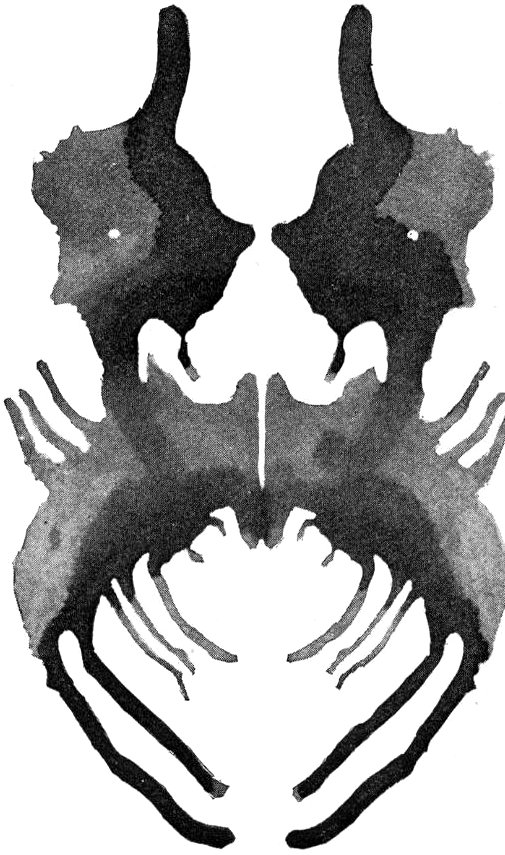

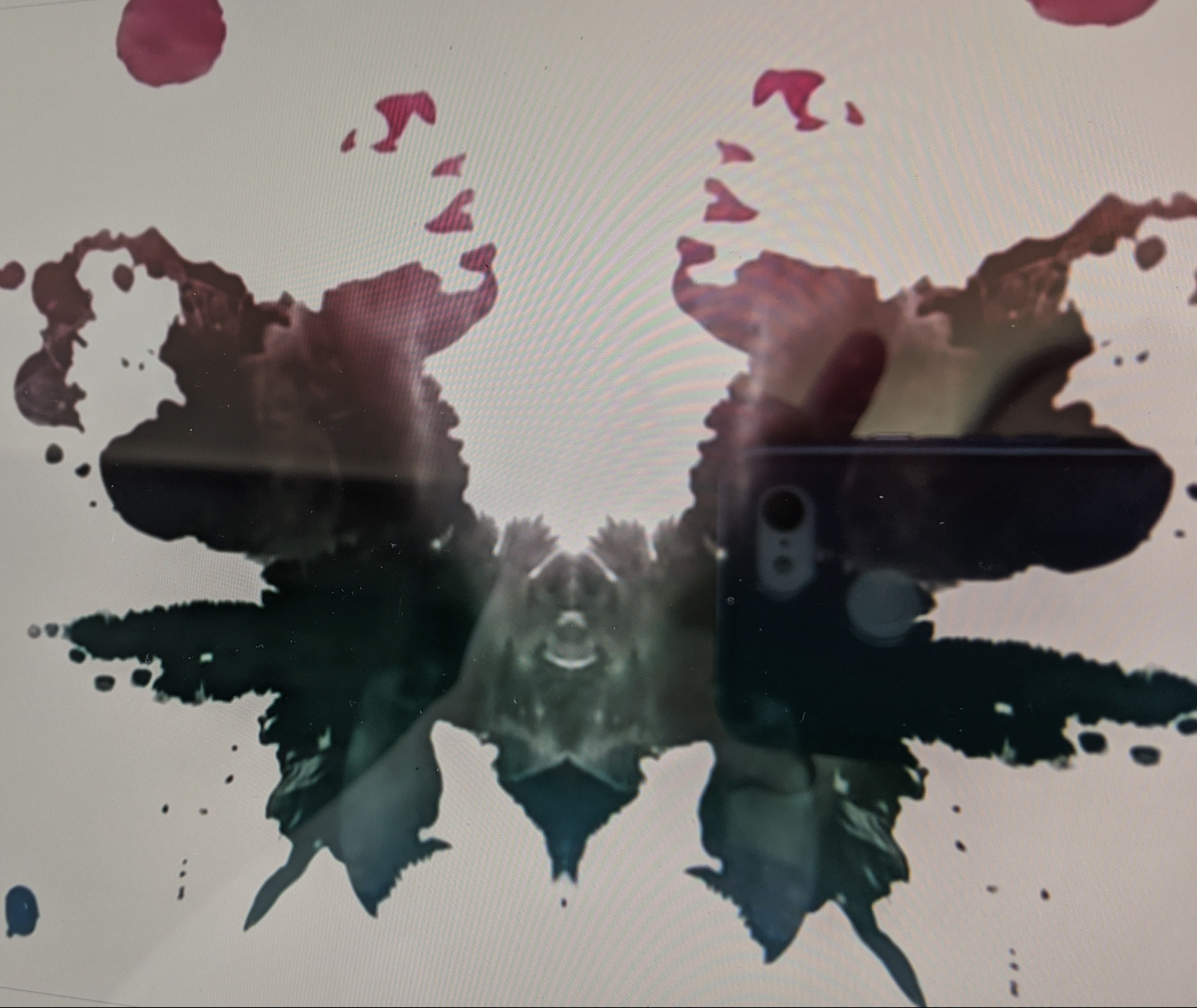

Blotto or Gobolink is a poetry game from the 19th century. Players make up poems about what they see in inkblots and then read them to each other. Details are here.

Make your own inkblots, use this one, or find some here.

If you don’t have ink and want to make your own blots, try runny paint, a dark juice, tea, or coffee.

Study your blot. What do you see in your chosen blot? Can you name some shapes, sizes of shapes, numbers of shapes? (For example: dozens of teeny dots, seventeen circles, many small moons). What does the blot remind you of? How does the blot (and what it reminds you of) make you feel? If it could tell you something, what would that be? How would you answer? What will you do next? You could make each answer a line of your poem, follow this template, or go your own directions! Each step of the template might involve more than one line of your poem.

- Pretend you are in the blot. Say where you are.

- List what you see around you.

- Say how the blot makes you feel.

- Say what the blot reminds you of.

- Say what the blot would tell you, if it could.

- Say what you would answer.

- Add a surprise that isn’t about the blot.

Arrange your lines. Decide which belongs first, last, and so on.

Example poem:

The Somethings by Ruth McEnery Stuart And Albert Bigelow Paine

AhmmmAAAzing inkblot video of a favorite song of mine. (Not necessarily child-appropriate… here for the teachers and parents.)

Activity link:

Wonderful ink blot activities from Margaret Peot, author of Inkblot: Drip, Splat and Squish Your Way to Creativity (Boyds Mills Press, 2011)

An excellent book from which I learned about Blotto, the 19th century poetry game:

5. A DREAM POEM

This poem could be about a dream you remember or a wish for the future.

What did you see? What colors? Are you alone? Do you know where you are? What are you feeling? Why do you think you’re feeling this way? What are you doing? How are things (people, places, sights, smells, sounds, etc.) the same or different from here and now? You could make each answer a line of your poem, follow this template, or go your own directions! Each step of the template might involve more than one line of your poem.

- Shut your eyes for a moment and think of your dream

- Name something you see in your dream. Give it a color or size or both.

- Name another thing you see. Give it a color or texture or both.

- Tell if you are alone or with others.

- Say how the dream makes you feel.

- Tell what you wish about the dream. (That it last longer, never happened …)

- Describe a smell or taste or sound from your dream.

- Name a strange/magical thing from the dream.

Dream Song

by

Walter de la Mare

Sunlight, moonlight,

Twilight, starlight.

Gloaming at the close of day,

And an owl calling,

Cool dews falling

In a wood of oak and may.

Lantern-light, taper-light,

Torchlight, no-light:

Darkness at the shut of day,

And lions roaring,

Their wrath pouring

In wild waste places far away.

Elf-light, bat-light,

Touchwood-light and toad-light,

And the sea a shimmering gloom of grey,

And a small face smiling

In a dream’s beguiling

In a world of wonders far away.

This is one of my favorite dream poems, by Langston Hughes.

6. A POEM OF DIRECT ADDRESS

Make a poem that speaks to someone or something. Call the someone or something, YOU. As in “Twinkle, Twinkle,” think about what you know about the YOU you choose.

Here’s a template to play with or ignore:

- Choose your someone or something. The YOU of your poem. The YOU can be a friend, a flower, your own nose–anything or anyone.

- Imitate “Twinkle, Twinkle,” by starting with a repeated action of your YOU. 1st line: Action, action, YOU.

- 2nd line: Say how you feel about your YOU. (A strong emotion.)

- 3rd line and 4th line: Describe two or three things about your YOU. Such as where or when you are together, or what you do together. Or, why are you apart?

- 5th line: Ask your YOU a question or two.

- 6th line, jump into the future. Say where you and YOU will be.

- Repeat your first line.

Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star

Twinkle, twinkle, little star,

How I wonder what you are.

Up above the world so high,

Like a diamond in the sky.

When the blazing sun is gone,

When he nothing shines upon,

Then you show your little light,

Twinkle, twinkle, all the night.

Then the traveler in the dark,

Thanks you for your tiny spark,

He could not see which way to go,

If you did not twinkle so.

In the dark blue sky you keep,

And often through my curtains peep,

For you never shut your eye,

‘Till the sun is in the sky.

As your bright and tiny spark,

Lights the traveler in the dark.

Though I know not what you are,

Twinkle, twinkle, little star.

Twinkle, twinkle, little star.

How I wonder what you are.

Up above the world so high,

Like a diamond in the sky.

Twinkle, twinkle, little star.

How I wonder what you are.

How I wonder what you are.

- A LEXICON POEM

You know more about some things than anyone else in the world. Those are what lie in your mind, in your dreams, in your thoughts, and in your memories.

You also know more about some things than many other people do. Those are what you have investigated or studied or lived with.

Make a poem using the words connected with one of those familiar-to-you things. This list of words is a lexicon, language special to a topic or person or place.

What is your something? Maybe it is a hobby. Maybe it is something you study. Maybe it is a game you enjoy. Maybe it is a memory of a trip. Even if others were on the same trip, their memories, of course, are different from yours. List actions it involves. List objects special to it.

For example, my mother used to embroider. Her lexicon might have looked like this: action words–sew, stitch, knot, cut, stretch, thread, prick, pull; object list–linen, yarn, scissors, needle, hoop, thimble, pattern.

My mother embroidered this pillow for my grandmother who loved strawberries.

Here is a template to follow or ignore, with examples from embroidery:

- Start a new line with each action from your list.

- On each of those lines, include one or more of the objects from your list that goes with each action. Add action words to match objects, if you wish. Example (A slash(/) means there is a line break here.): Sew a pattern/ Stitch a line/ Don’t knot the yarn/ Cut the yarn/ Stretch the linen in a hoop/ Try not to prick your finger/ Wear a thimble/ Thread a needle/ Pull the yarn through

- Name or make up a rule about the thing. Example: Start sewing from the center of the cloth.

- Arrange the actions in the order that they happen. Stretch the linen in a hoop/ thread a needle/ sew a pattern/ pull the yarn through/ stitch a line/ don’t knot the yarn/ cut the yarn

- Play with repeating an important action, or two, to pattern your poem. Example: Sew, sew, sew. Snip, snip, snip.

- Arrange! Add. Subtract. Repeat. Play. Title your poem. Example:

My Mother Used to Embroider

Stretched linen in a hoop.

Threaded a needle.

Sewed a pattern.

Pulled the yarn through.

Stitched, stitched, stitched.

Didn’t knot the yarn.

Cut the yarn.

Snipped, snipped, snipped.

Started in the center.

Here’s a limerick by Leigh Mercer that shows off a math-y lexicon (and describes this equation):

A dozen, a gross, and a score

Plus three times the square root of four

Divided by seven

Plus five times eleven

Is nine squared and not a bit more.

A variation on the lexicon poem is to use a lexicon for an unrelated topic. For example, what happens if an embroidery action lexicon drops into a poem about skiing? “Cut a path through the powdery snow,” “Sew a line down the slope,” “Thread through the trees.”

Make a few lexicons. Experiment with dropping them into poems about unrelated topics.

A poem by Emily Wheeler, “Lexicon.”

8. A TWO-MINUTE POEM

This poem follows a template:

The results may make you laugh! I hope they do.

Ways to play with this template:

… Substitute your lexicon from poem lesson 7.

… Add new words to the lists. Maybe all your words contain an A or an O, some sound that links them.

… Treat the template like a game of Mad-Libs with folk in your household. Use the words given or your own.

Resources:

This website has a giant Mad-Lib poem generator!

This website has a list of poem forms/templates to investigate.

This page suggests removing nouns and verbs from a poem and replacing them with your own. Remember always to credit your source. After titling your poem say, “After …” and name the poem and poet.

9. PATTERN POEM

Make a poem from a pattern.

Here’s a template to play with or ignore:

- Choose five colors or shapes. Call each a UNIT. The units in the example, below, are black, yellow, red, green, and blue.

- Create a design or pattern in which you use one unit thrice, three units twice, and one unit just once. (You can always repeat your pattern to make the poem longer.)

- Draw your pattern.

- List 4 true things about a topic. Match each true thing to a unit.

- List a 5th true thing that only you know about the topic. It could be how you feel about your topic, what you hope for it, what you dream about it, or something goofy like what you would tell it if it were your friend. OR … Would you like this line to be a question?

- Arrange your list of true things so it matches your pattern of units. Play with the list until you like the sequence.

Here is an example poem using the pattern above.

It might be fun to switch the last period of the poem for a question mark. It’s fun to make tiny changes that change the meaning.

I thought of this poem-at-home idea after color-coding the pattern for a form of poem called a pantoum. I printed my lines and cut out each. I tried different lines in the pattern on this sheet, pictured below, until I had the arrangement I wanted.

Here’s the finished poem.

10. A LOVE POEM

The idea today is love. If you want to make or use a template, decide first who is your person of focus? Each number (below) is a line of the poem. The poem could be of direct address—to the person like this David Anderson poem:

- Person, Person

- I love you.

- I love the way you…

- bc it feels…

Or the poem could be about the person like this Langston Hughes:

- I love ______

- She/he/etc. lives ___________

- I love ________because ____________

- If ______were here I would _____________

Here are some questions/prompts to mix and match for your own template, or to use to launch something with a looser shape, length, etc.

I. What I love about you/ ______:

3. I love the way …

4. I love you/______ more than …

5. What is love?

6. What do you do for someone you love?

7. How do you know you love someone?

8. How do you know when someone loves you?

9. Where do you feel love?

10. What can you do to spread love /show that you love the person? Where does love take you?

11. How big /strong /powerful /deep /happy … Is your love?

12. What do you wish you could do to show your love?

Here’s a video of me with Bret Ellerton, director of New Discovery School in Seattle, Washington, describing presenting this as a lesson to young children. If you have questions, please, ask through my contact page. (The part about phone calls was only for the teachers of NDS.)

Happy Valentine’s Day!

11. A SOUND POEM

Some poets call these abstract poems and claim that their most important aspect is how they sound, not what they mean, and they may be non-sensical. Others will claim the sound makes the meaning.

Here Zoe Van-de-Velde gives a wonderful description about how to go about making an abstract poem.

My how-to suggestions are for not-yet-independent writers. They’re not elegant. They’re goofy and pretty hard to follow. I agree with Susan Landgraf who believes rhyming is work for advanced poets.

Here’s a template to follow or ignore:

- Choose three animals. (For example: a) ladybug, b) horse, c) eagle.)

- For each, make up something completely impossible or silly for them to do. Rhyme the lines if you can. (For example: a) Ladybug sings from her rocking chair. b) Roan horse yells, “Who’s up there?” c) Eagle wishes for a birthday fair.)

- From each sentence, take the last word and the verb to rhyme twice or thrice. The rhymes can be made up words. (Example: a) sings and chair–Mings rings swings–flair tair zair! b) yells and there–Bells dells pells–flair tair zair! c) wishes and fair–Lishes fishes prishes–flair tair zair!)

- Alternate the lines from 2 with the lines from 1. (Example: Ladybug sings from her rocking chair./Mings rings swings–flair tair zair!/Roan horse yells, “Who’s up there?”/Bells dells pells–flair tair zair!/Eagle wishes for a birthday fair./Lishes fishes prishes–flair tair zair!)

Many children’s books and songs and even some lines of Shakespeare might be categorized as abstract or sound poetry. Here are a few examples:

From As You Like It by William Shakespeare:

It was a lover and his lass,

With a hey, and a ho, and a hey nonino,

That o’er the green cornfield did pass,

In springtime, the only pretty ring time,

When birds do sing, hey ding a ding, ding;

Sweet lovers love the spring.

Here is Chicka Chicka Boom Boom in its entirety:

This is a FABULOUS example of an abstract or sound poem: “On the Ning Nang Nong” by Spike Mulligan. This would be fun to illustrate.

Here is a less non-sensical poem by a poet who loved to write abstract poems:

Interlude by Edith Sitwell Amid this hot green glowing gloom A word falls with a raindrop's boom... Like baskets of ripe fruit in air The bird-songs seem, suspended where Those goldfinches—the ripe warm lights Peck slyly at them—take quick flights. My feet are feathered like a bird Among the shadows scarcely heard; I bring you branches green with dew And fruits that you may crown anew Your whirring waspish-gilded hair Amid this cornucopia— Until your warm lips bear the stains And bird-blood leap within your veins.

12. AN ABECEDARIAN POEM

This form relies on the alphabet.

Choices:

- Make a 26-word poem, the first word beginning with A, etc.

- Make a 26-line poem, the first line beginning with A, etc.

One approach is to name a topic in the title and treat the title as if it starts each line. The lines then become descriptions of the topic or tell actions of the object.

A fun part is coming up with words to fit the “weird” letters. X is always an issue! A dictionary is handy.

An example of the 1st choice (which I think it trickier than the 2nd):

Penguin Abecedarian

Antarctic-dwellers brave

cold days; endless frozen ground—hard, icy;

jostling; killer leopards—monstrous notable oceanic predators;

quarrels; raging snows; temperatures under—!!!;

vortex white-outs—xiphoid yowling zeroes.

This site includes abecedarians written by children:

http://blueskybigdreams.blogspot.com/2012/04/abecedarian.html

This beautiful sample of an abecedarian (for mature readers) refers to its form:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/55645/a-poem-for-s

13. A POEM PLAY

In this fun article, the author suggests acting out poems. We may understand them better if we do. The students in this article are older than the children I most often see, but, I think the three-, four-, and five-year-olds would not only enjoy acting out poems, but would, like the older students, more fully grasp what they are about.

Immediately I pictured half the children being catfish and the other half being humans looking into the pond of Richard Brautigan’s “Your Catfish Friend,” and in “Poem” by Langston Hughes, that the children face each other in a circle until “He went away from me,” when they would turn to face away from each other, and at the repetition of “I loved my friend,” turn back to face each other again.

In the classroom, we often move to poems, as in waving our arms overhead during Christina Rossetti’s “Who Has Seen the Wind,” or accompany our recitations with exaggerated American Sign Language in Karla Kuskin’s “There Is a Tree that Grows in Me.” As much as possible I try to think of ways to include physical activity on my poetry visits. I ask the children to stand for most recitations, or stamp their feet in rhythm. I’m going to argue that such abstracted motion might help small children experience some of the abstract aspects of the poems. Certainly, the music of the verse will be more obvious to a child stamping her feet to the beat of a poem, than to the child sitting still.

Now to make a poem suitable for acting out.

- Choose three characters—people, animals, objects …

- Give each words to say about the same thing—weather, a holiday, an important happening …

- Have that thing respond.

- Act it out. Find places to add movements unspoken but implied.

Example:

HAWK WAITS FOR THE WIND TO BLOW

In spring the grass says, I am green. (NARRATOR and GRASS)

Cow moos, You are mouthwatering. (NARRATOR and COW)

Overhead, a hawk, on the wing, (HAWK)

asks, What mice are your blades hiding? (NARRATOR and HAWK, MICE HIDING)

Grass says, Wind will show you many. (NARRATOR and GRASS)

(WIND BLOWS, HAWK POUNCES, MICE RUN)